The parser is pretty much done :D I only have a couple non-terminals left to finish, and of course all of the bugs to iron out, but I never thought I would get to this point! So happy right now.

To sort of immortalize how I spent the last two weeks of my time, I’m documenting my workflow for writing the parser. I noticed I very quickly fell into a couple of patterns, and I fell into a certain flow of work with it. Which I thought was cool!

If you want to dig into the code, it’s hosted on GitHub.

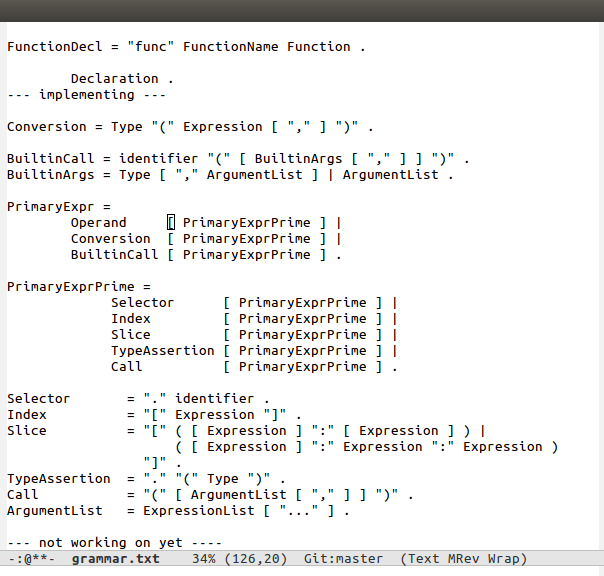

grammar.txt

First I delineate which part of the grammar I want to implement. After writing the test cases for it, I determine the top level terminal sets for the non-terminals. A top level terminal set is the set of all terminals that a non-terminal can start with (I’m also 90% sure I made the phrase up.) For instance, the top-level terminal set for Index is “[“, and the top level terminal set for PrimaryExprPrime is the union of the top level terminal sets of Selector, Index, Slice, TypeAssertion, and Call.

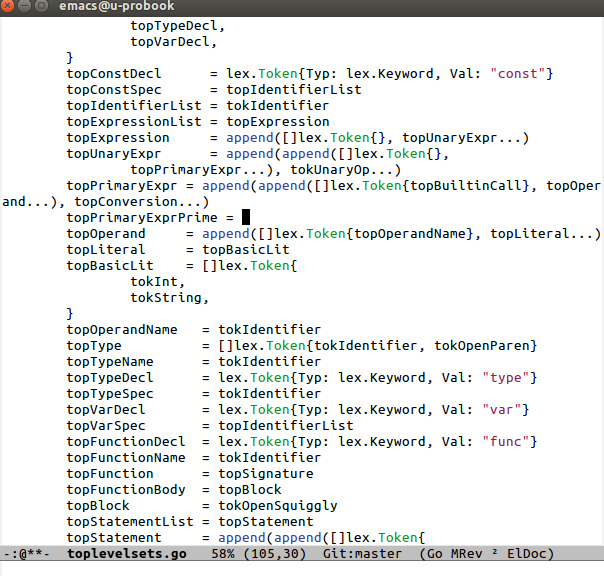

toplevelsets.go

As you can see, top level sets can be very clearly defined in Go as slices of tokens (if you are unfamiliar with Go, slices are lightweight, resizable arrays.) The append calls simply take a slice and append any number of arguments to that slice. The “…” syntax takes a slice of tokens and splats it as a set of arguments. I use those together to create slices of tokens from other slices. I don’t worry about redundancies: I’m more concerned with communicating the meaning than having the top level sets be as efficient as possible.

This work is done in a top-down fashion: I write the most general of the non-terminals’ top level sets first, creating them from the top level sets of their child grammars.

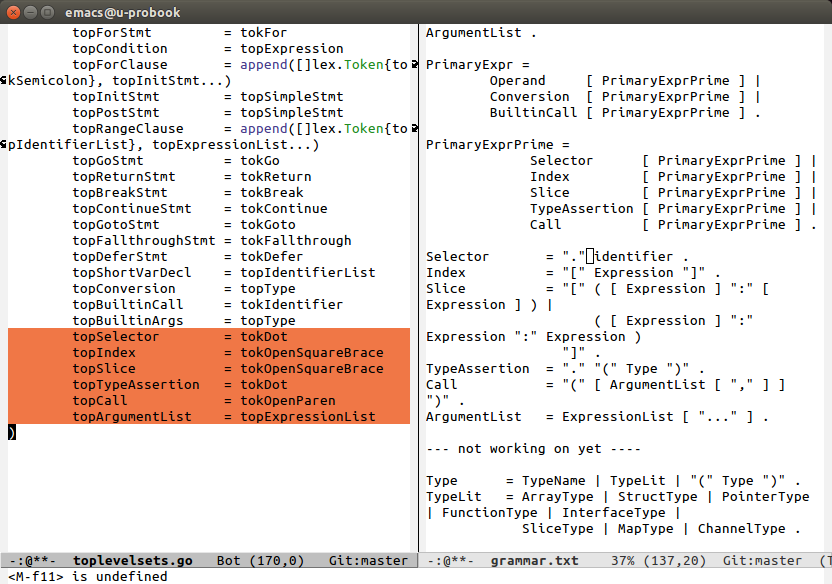

toplevelsets.go

You can see how the specification for non-terminals is clearly reflected in the syntax for the top level sets in Go.

Creating the top level sets is not challenging, and is more of an exercise in remembering which top level sets are plain tokens, and which are slices of tokens, so I can combine them with the correct syntax.

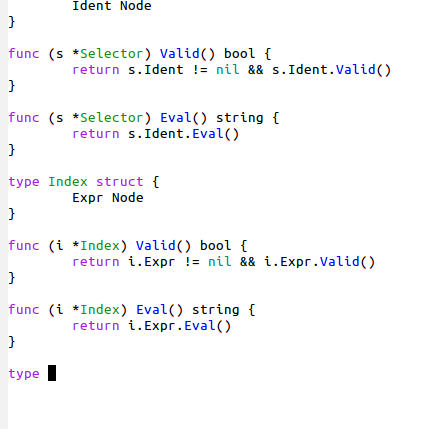

nodes.go

Then I create all of my node types. Nodes are defined by the following interface:

type Node interface { |

Interfaces in Go are similar to interfaces in Java, or pure abstract classes in C++. For a type to fulfill the interface Node, it needs the function Valid() that returns a bool, and Eval() that returns a string. Valid is used to check that a node and its child nodes are constructed correctly. The Erro type always returns false, terminals and simple nodes return true, and all other nodes return true if all of their child nodes also return true and the node itself is well formed. A well formed node is a node that has all the children that are required of it by the grammar.

At first, I did not have the Valid method defined for nodes, but I needed to define it in order to implement backtracking later in the project. By the time I realized I needed the Valid method, I had already defined forty different nodes. It took a lot of willpower and about an hour of emacs/regex magic to create all of the Valid methods :)

The nodes themselves follow pretty easily from the grammar. Almost every non-terminal has its own node because I didn’t want to “simplify” and reduce the number of nodes I had before I had understood how the grammar worked. I’ll chop them down in a refactor.

This is also done in a top-down fashion: I create the more general nodes first and define them as combinations of their child nodes (though the Node type is general, the names I use for a node’s children are significant.)

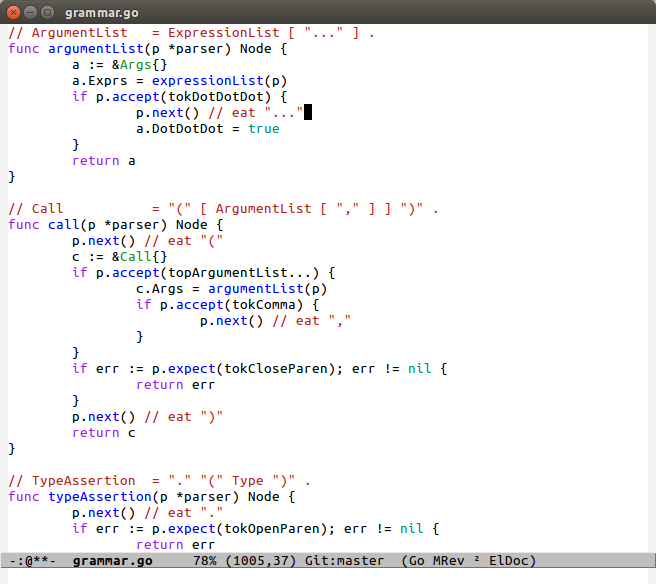

grammar.go

This is core of the parser, the bit that is actually recursive descent :) This part is also the most fun to write. Each non-terminal gets a function with the same name, but starting with a lowercase letter. Keeping the names consistent with the grammar.txt makes writing the grammar really easy, and makes it easy to see how the grammar function follows from the specification.

If you look at ArgumentList, you can see it consists of an ExpressionList and an optional “…”. This is reflected in the function directly: First, and Args node is created, and then expressionList is used to create the Args’ child node, Exprs. Then, you check to see if the next token is “…”. If it is, then the token is thrown away with the p.next() call, and the DotDotDot field is set to true for Args. Then the node is returned.

Notice how I didn’t check to make sure that it was valid to create an ExpressionList by calling expressionList. Each function assumes that it is in the correct state when it starts, and you must check to make sure that you can start parsing a node before you call the function to create it. This invariant simplifies the code, and is a lesson I learned from writing my lexer, where I did error-checking before and after entering new states.

conclusions

To quote a fellow hacker schooler, “parsers take a while.” This took two weeks, and while I’m happy with how much it parses, it doesn’t parse the entire language, and I’ve yet to shake out all of the bugs. But I’m incredibly happy with what I’ve finished: there was a point where I didn’t think I would finish the parser at all, especially towards the end as I started tackling larger parts of the grammar like statements and expressions. Can’t believe I made it through :) I learned much more about dealing with frustration and tedious work than I thought I would. Parsers are a lot of work!

Having wrapped up my parser, I will never feel guilty for using a parser generator in the future :)